Well, here we are: the final blog. Fourteen weeks have passed and we’re ending it with the spectacularly spunky Run Lola Run. Run Lola Run was released in 1998, written and directed by Tom Tykwer, and stars Franka Potente as our protagonist. The plot of the movie surrounds Lola’s mad dash to come up with the 100,000 marks to save her boyfriend’s life in 20 minutes. In reality it’s more like Manni requests that Lola comes up with the money he lost to “pRovE HeR LoVe” for him or else he’ll take the easy way out and rob a bank himself. So Lola does what she must and attempts to find him the money some way, although it takes her two repeats to get it right; almost like a video game. Now, this isn’t the first time I’ve seen Run Lola Run. It was first shown to me in a freshman art class and I remember instantly thinking it wasn’t like any movie I’d seen before. That’s because Run Lola Run has a little bit of every genre in it: action, drama, adventure, romance. Not to mention stunning and unusual visuals, including an animation sequence that helps explain the time jumps in Lola’s journey. One of the aspects I enjoyed in Run Lola Run was the side-story snapshots of the background characters that Lola encounters, I really think it adds to the uniqueness of the film. In class we talked briefly about cinema du look, this combined with the running shots and jump cuts felt similar to the movement. But my favorite part of the movie was its aesthetic. It’s obvious that the movie holds a style that is unique to movies coming out in the late 90’s, the fashion as well as general look is easy to pinpoint, I might as well mention the similarities in Lola’s appearance and Leeloo’s in The Fifth Element.

One thing that stuck out to me after reading the Kosta essay on Run Lola Run, was the comparison of the movie’s narrative timeline to that of a video game as well as a cartoon. We all know that Lola gets three tries to get the money and meet Manni but it’s more than just a time jump. It’s like she has a certain amount of lives, when one is used up she must reproach her strategy and try again. I thought it was also interesting to compare the movie’s realm of reality to that of a cartoon considering there is animation already added into it. When you think about it, though, the movie does in fact imitate the fantastical worlds that we often see in cartoons. Characters have superpowers or events are exaggerated, Lola breaks glass with her scream, and situations are amped up to make for a more exciting outcome. So Run Lola Run really does feel a lot like watching a live-action cartoon.

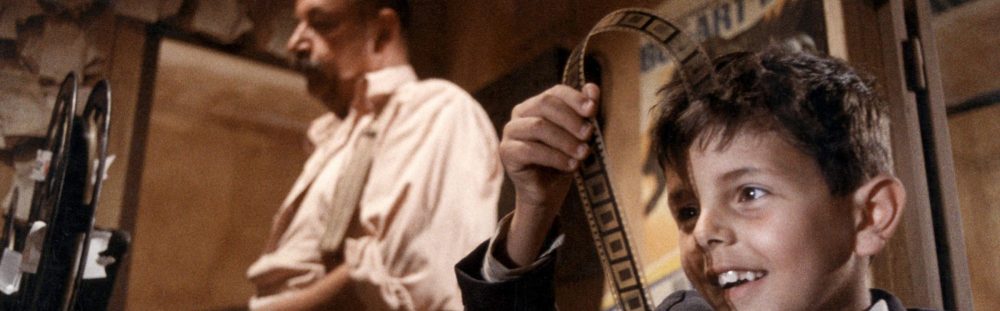

It’s weird to think the semester is already over; time flies, right? The history of the motion picture, a trip from the development of film technology to a full-blown story telling medium. There was so much information packed into this course that it’s hard to believe we really started with the very beginning of film. If I were to pick my favorite topics discussed this semester it would come down to Italian neorealism, 80’s body culture, and the exploitation film & midnight movie circuit. In all of these topics we were able to see the depth that film reached as a diverse medium. In neorealism we see a different approach to storytelling through cinematography and narrative. In the week of 80’s body culture we looked at the way society influences the movies being created at the time. In exploitation we learned about the industry and the more alternative side of Hollywood. This course not only provided us with a vast array of lenses to view movies through but it also provided us with the skills to continue our learning.

As a naturally indecisive person I will not be choosing just one favorite screening as I cannot do that, so I will choose my top three instead. The first will have to go to Wild Strawberries, this was one that I enjoyed on multiple levels. I loved the look of the film, it’s dreamy feel, and the story itself. I had been awaiting when I would watch a Bergman film and this one did not disappoint, although I have yet to see more. I also related a lot to the existentialism of the film, so that definitely added to my enjoyment. My second favorite screening was The Bride of Frankenstein, what can I say? I’m a sucker for camp and over-the-top set design. What I really enjoyed about it was that it made me laugh, there were so many little things to love about it. And the big reveal at the end of the bride herself was enough to secure its place in my top three. My third and final favorite screening has to go to The Fly, any movie that can pull a visceral reaction out of me is one that I will remember. I also really enjoyed the concept of the abject in our discussion that week.

Another film class down, and a new minor added. Here’s to the next one!