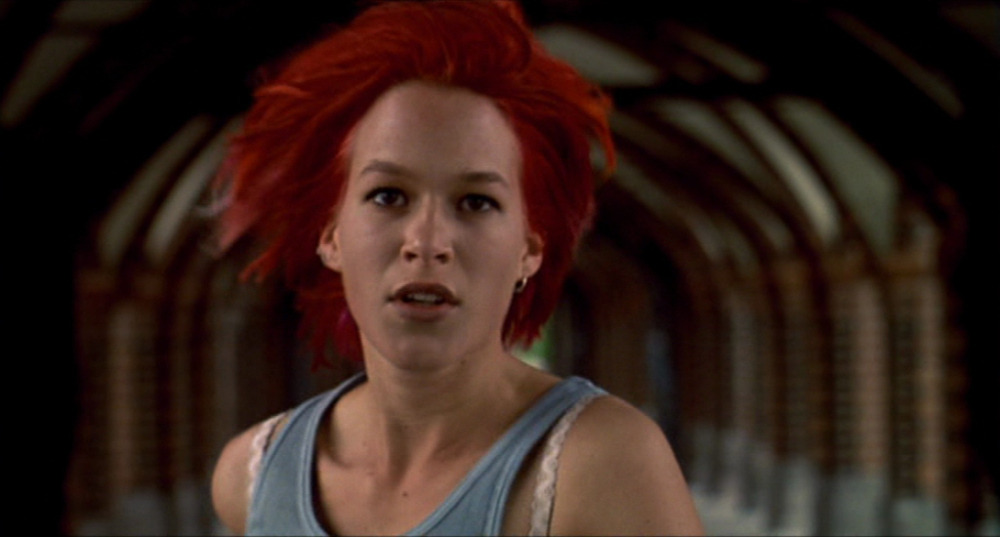

Tom Tykwer’s film Run Lola Run is phenomenally directed, and Mathilde Bonnefoy, in particular, did an outstanding job in the editing department, as the film is just fine filmed with a fast pace that is entertaining rather than tiring, and it is still beautifully energetic and riveting with very seamless transitions between the repeated scenarios. It’s still very well taken, with some great action scenes, and after being repeated twice, the main character’s running never gets old. It has some unforgettable imagery and strong dialogue. The characters scream excessively, but they are nevertheless portrayed realistically. Without a doubt, this is one of the most original and fascinating films of the 1990s.

Lola is played by German actress Franka Potente, a young lady who runs the whole duration of the film without exhibiting any signs of exhaustion.

This demonstrates Potente’s outstanding physical condition before filming began. Potente does an excellent job of keeping Tykwer’s concept alive and well. Franka is a standout in this movie. Her overall screen appearance is as effervescent as ever, and it’s not just because of her fiery locks. She commands attention without saying anything.

She was already young and in the early stages of her acting career when this film was released, so Run Lola Run served as an excellent vehicle for her, propelling her to bigger roles in the future.

She gives a great performance and puts in a lot of effort in her role. With all of her contributions, and with Tykwer as director, she is the true star and the driving force behind the film “Run Lola Run.”

The film never really discusses what is going on – how Lola is given a second chance on this particular day, and another chance to play it out – but that isn’t always a bad thing. It’s much more interesting to watch Lola try to achieve her goal, which is shot and handled with extreme precision.

Another thing that struck me from the outset of the movie, whether it was the red hair or the red phone, was the film’s monotonous colour scheme. The team is called the Reds. Veggies. Yellows are a bright color. Over and over again, and right in front of your eyes. Tykwer wasn’t going for subtlety; he wanted to deliver a straightforward and unmistakable message–another connection to time. Yellow would work right in as a slowing of time or even a difficult choice that must be taken, so red simply means stop and green clearly means independence or go.

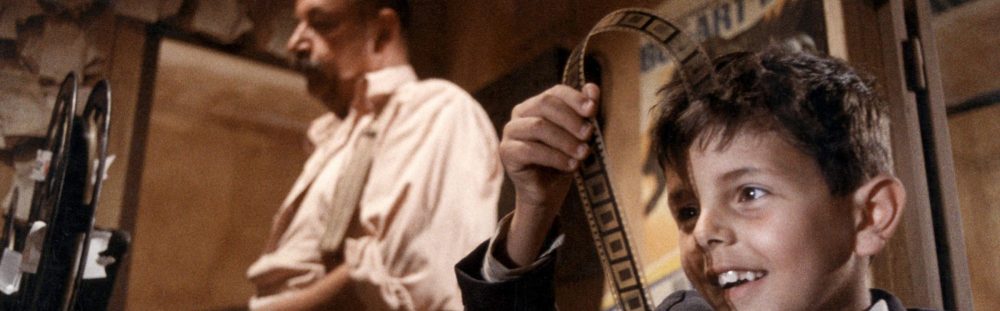

Reflecting on this semester, I heavily regret the weeks that I didn’t write a blog. It’s a great allegory for how this semester has gone in that I wound up procrastinating things I actually enjoy, and it would consequently be painful. What can ya do. I wish I had written about The Fly in all its glorious grotesqueness, as it was one of the films that founded my interest in horror (horror movies were too scary but 80s horror? Just right for some reason) As well as Geena’s Davis’ ingenious acting. I also regret not writing about Ruggles of Red Gap because it was genuinely unlike anything I’d ever seen before, and incredibly hilarious. The comedic timing still resonates and I found myself wondering constantly about what being a part of the film industry in 1935 would have been like, especially for funny women.

I quite loved L’avventura and told my parents to watch it immediately because they’re the type of Italy-lovers that love to point to the cathedrals and capes that they recognize.

Only such a beautiful scenery and tone could balance out the moody actors and actresses, sulking on the meditteranean. Grand Hotel was so classically beautiful, and an interesting comparison to how many times my sister has made me watch The Grand Budapest Hotel. Something about hotels, they’re so subliminal and dreamy. The concept of the big three Hollywood studios interests me so much, especially after watching Hail Caesar! By the Coen Brothers. So much drama, like 90210 but with pacific northwest accents.

My favorite week was definitely Bonnie and Clyde. It was such a beautiful film that encapsulated so much teenage angst, freedom and rock and roll with a gnarly shootout at the end. Some films hit you right in the heart, and this was definitely one of them.

Pauline Kael puts it perfectly, “puts the sting back in death” and I would say brought some sexiness to the Depression in which it was set. Weirdly it mimics the star-crossed but destructive lovers of Sid and Nancy which was also my favorite film of the course from cult movies, though both films were very differently gut-wrenching.

Meeting Joe Dante was also a highlight of this class, and really felt super cool to have him tell me some films by name that I could watch from his era of inspiration. I’m always looking for new sources, and Gremlins weirdly pulled me out of a funk that I’d been in. It’s almost like the absurdity of it made me realize how absurd what we are dealing with right now. Like, just continuing on with classes and life as if it’s not a constant struggle. Reminds me of the scene where the girl is just going crazy trying to serve all the Gremlins in the bar, and trying to take their orders and give them drinks, like it’s gotten to a point where we don’t even notice how absurd this all is.

Not to be too abstract, but I am very grateful for these foundational films. I’m hungry to watch things out of the context of school for the summer, but only because I will have so much time to look back on what I’ve wanted to see this year. I feel like I’ve grown from my disappointments, and that my writing has persevered a bit. Thank you to everyone for reading and commenting on my blogs with their silly little titles. I get a lot of joy from putting this work out there, and it feels good to have it perceived.